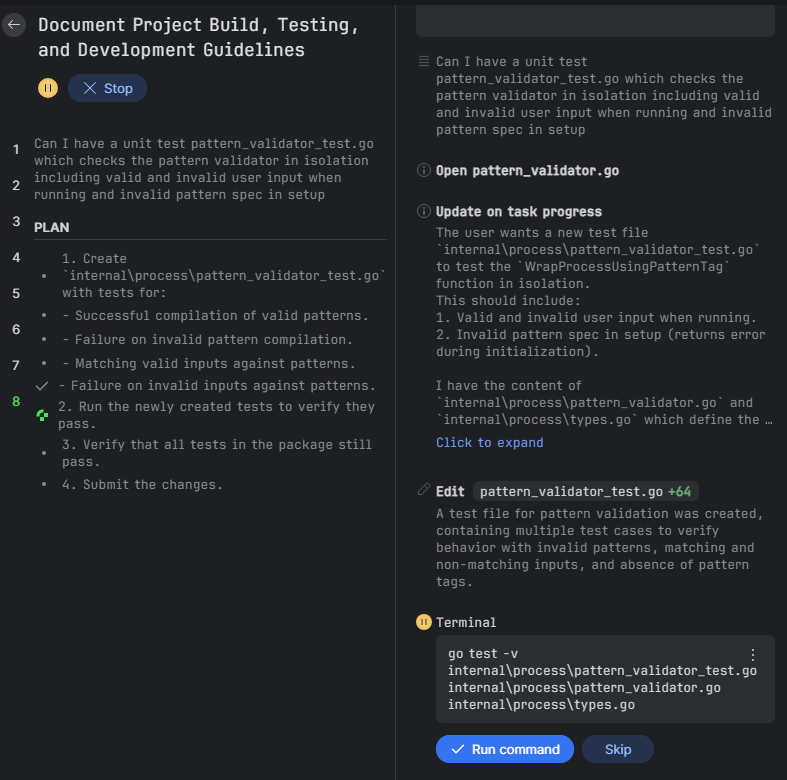

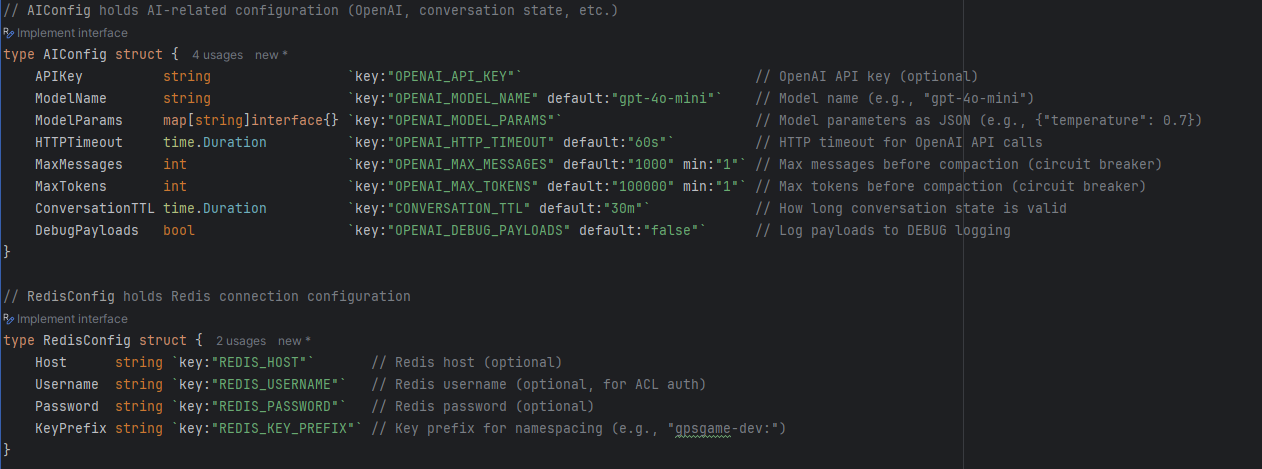

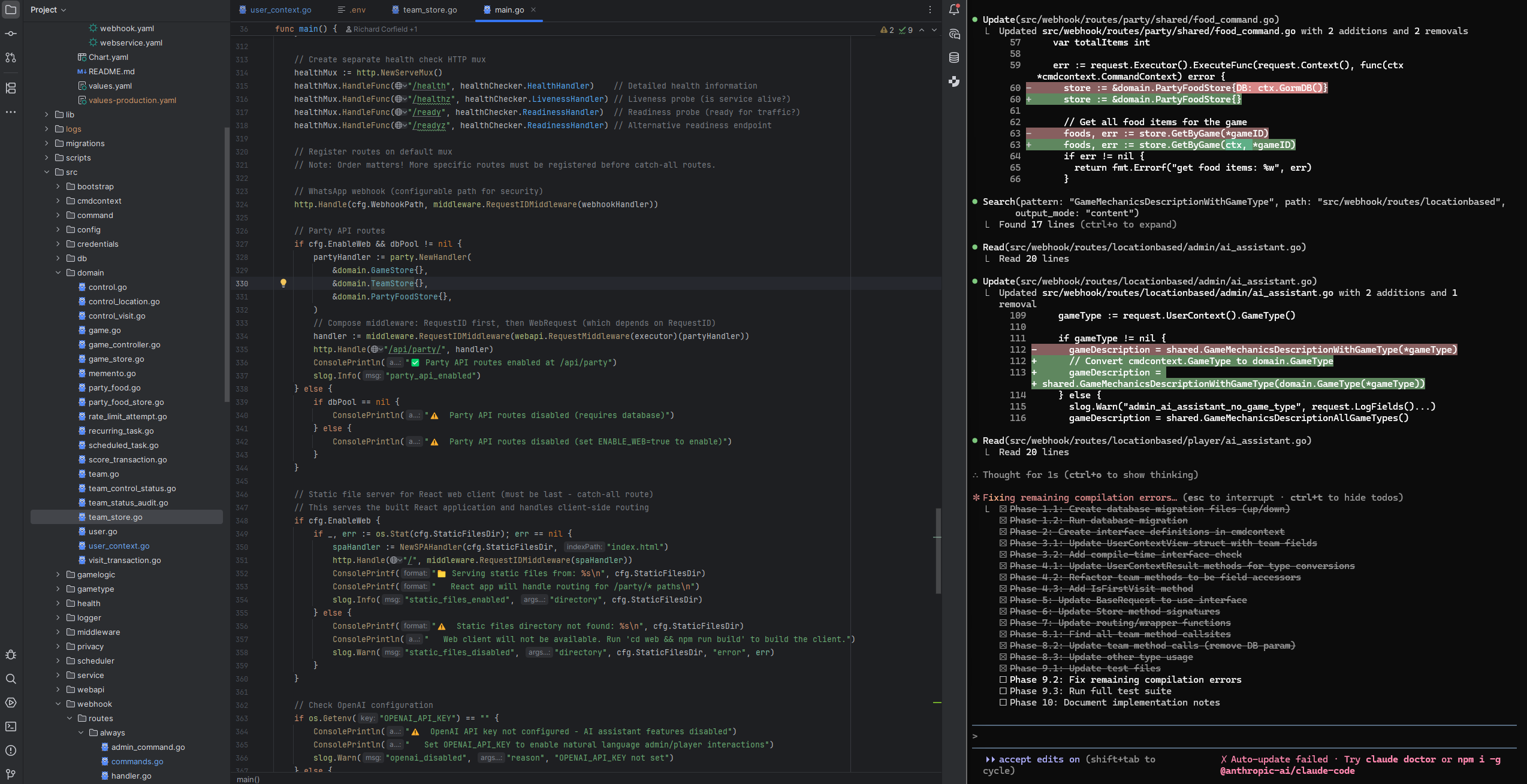

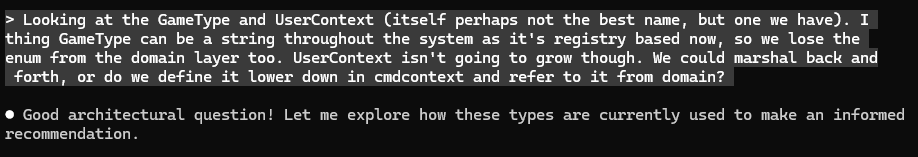

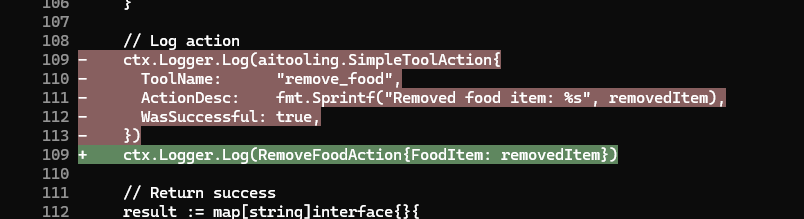

I’ve had less time over Christmas to work on it, but am progressing. My relationship with Claude Code is turning more supervisory. I’m often generating sample code and infrastructure/patterns for it to follow. “Make me a new Team Store like my User Store”.

This way I have set up the working pattern for Domain, Store, Busines Layer and Presentation. I now have a strategy which I believe is more maintainable and allows for testing.

The Domain Layer – Static Stores

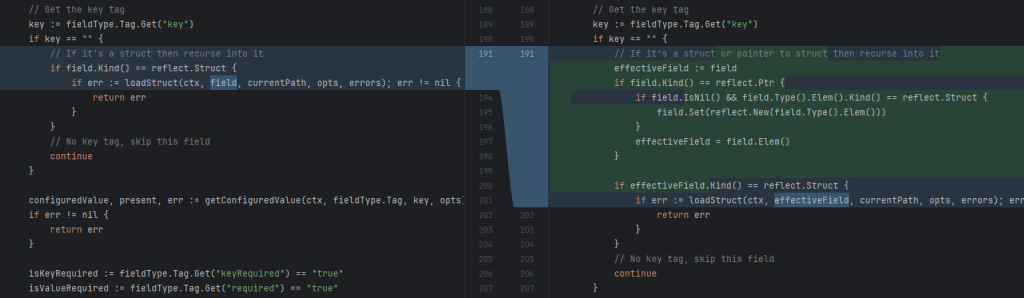

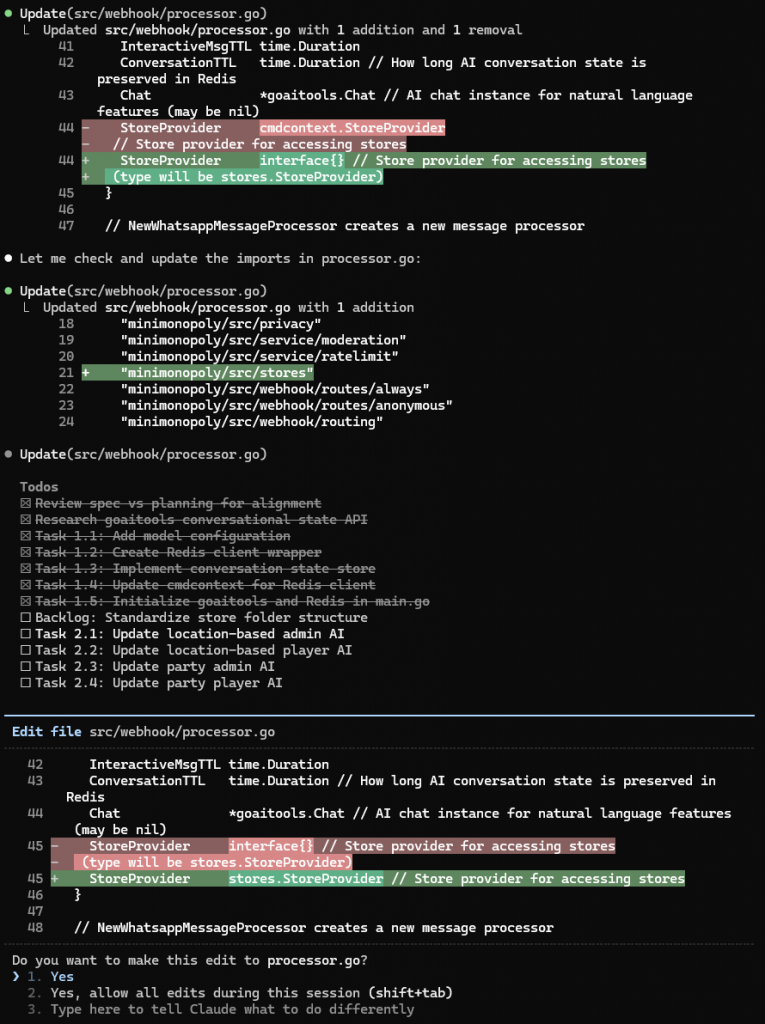

The first infrastructure made by Claude had used dependency injection to pass store interfaces down through the layers. This resulted in a StoreProvider interface to reduce the amount of parameters to pass around, and a lot of effort. Changes I’ve made:

- My Stores are packages full of static methods.

- My CommandContext interface has been broken out into specific HasGormTransaction and HasRedisConnection. The stores are coded to accept the one (or both) they need. This makes testing easier. (In my first article, Experiments in Go – Three Tier Architecture in a WhatsApp Game-Bot, I discussed how I use a Command Pattern to place control of transaction boundaries outside the business functions)

- I have a library of support code to make working with Gorm consistent and easier.

The idea is that the business layer should not be dealing with Gorm directly.

An example Store

This is the header of the User Store and the first method, GetById. The majority of the work is performed by the lower layer stores package. I’ve wrapped the Not Found error into a more specific userstore.ErrNotFound`. That’s likely the most complex piece of code here.

var (

ErrNotFound = errors.New("user not found")

)

type QueryOption = stores.QueryOption[domain.User]

type PreloadOption = stores.PreloadOption

func WithPreloadCurrentGame(options ...PreloadOption) QueryOption {

return stores.WithPreload[domain.User]("CurrentGame", options)

}

func WithPreloadLastControl(options ...PreloadOption) QueryOption {

return stores.WithPreload[domain.User]("LastControl", options)

}

func WithPreloadLastControlLocation(options ...PreloadOption) QueryOption {

return stores.WithPreload[domain.User]("LastControlLocation", options)

}

// GetById returns a user by ID. Returns ErrNotFound if the user is not found.

func GetById(ctx cmdcontext.HasGormTransaction, userId uuid.UUID, options ...QueryOption) (*domain.User, error) {

allOptions := append([]QueryOption{stores.Where[domain.User]("id = ?", userId)}, options...)

user, err := stores.First[domain.User](ctx, allOptions)

if err != nil {

if errors.Is(err, gorm.ErrRecordNotFound) {

return nil, ErrNotFound

}

return nil, fmt.Errorf("get user: %w", err)

}

return user, nil

}The store also provides methods to mutate the User. I’ve had to use the non-generic Gorm API here because the generic API does not make it easy to update set fields. There’s an issue raised against Gorm about this problem.

// SetContextToPlaying sets the user's current playing context to playing the given game.

// This store function does not validate that the user is a player of the game.

func SetContextToPlaying(ctx cmdcontext.HasGormTransaction, userId uuid.UUID, gameId int64) error {

updates := map[string]interface{}{

"current_context": cmdcontext.UserContextPlaying,

"current_game_id": gameId,

}

err := ctx.GormDB().Model(&domain.User{}).

Where("id = ?", userId).

Updates(updates).Error

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("set context to playing: %w", err)

}

return nil

}

How the magic works – the Stores package

Gorm’s generics interface is more typesafe. This includes different interfaces (gorm.Interface[T] and gorm.ChainInterface[T]) at different stages of the query building process. This makes using the Options Pattern harder. Here’s my Options structure:

type QueryOptions[T any] struct {

FirstOption FirstOptionBuilder[T]

Options []ChainedOptionBuilder[T]

Clauses []clause.Expression

}

type FirstOptionBuilder[T any] func(db gorm.Interface[T]) gorm.ChainInterface[T]

type ChainedOptionBuilder[T any] func(db gorm.ChainInterface[T]) gorm.ChainInterface[T]

func NewQueryOptions[T any]() *QueryOptions[T] {

return &QueryOptions[T]{

FirstOption: nil,

Options: make([]ChainedOptionBuilder[T], 0),

Clauses: make([]clause.Expression, 0),

}

}

func BuildQueryOptions[T any](options []QueryOption[T]) *QueryOptions[T] {

result := NewQueryOptions[T]()

for _, opt := range options {

opt(result)

}

return result

}

func (q *QueryOptions[T]) HasFirstOption() bool {

return q.FirstOption != nil

}

func (q *QueryOptions[T]) AddChainedOption(opt ChainedOptionBuilder[T]) {

q.Options = append(q.Options, opt)

}

func (q *QueryOptions[T]) AddClause(c clause.Expression) {

q.Clauses = append(q.Clauses, c)

}This results in options that have to be more intelligent about the kind of Builder that they create. Here’s the Where option

// Where creates a Query that applies a WHERE clause to the query

func Where[T any](where string, args ...interface{}) QueryOption[T] {

return func(opts *QueryOptions[T]) {

if !opts.HasFirstOption() {

opts.FirstOption = func(db gorm.Interface[T]) gorm.ChainInterface[T] {

return db.Where(where, args...)

}

} else {

opts.AddChainedOption(func(db gorm.ChainInterface[T]) gorm.ChainInterface[T] {

return db.Where(where, args...)

})

}

}

}I also have options for locking and preload. Preload takes a varadic list of PreloadOptions to customise preload.

One of the stores.Query method is

// BuildQuery builds a query from the given options

func BuildQuery[T any](ctx cmdcontext.HasGormTransaction, options []QueryOption[T]) (gorm.ChainInterface[T], error) {

var db gorm.ChainInterface[T]

opts := BuildQueryOptions[T](options)

for _, opt := range options {

opt(opts)

}

if !opts.HasFirstOption() {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("stores supporting layer does not support unbounded queries")

}

db = opts.FirstOption(gorm.G[T](ctx.GormDB(), opts.Clauses...))

for _, opt := range opts.Options {

db = opt(db)

}

return db, nil

}

// First executes a query and returns the first result

func First[T any](ctx cmdcontext.HasGormTransaction, options []QueryOption[T]) (*T, error) {

db, err := BuildQuery(ctx, options)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

var record T

record, err = db.First(ctx.Context())

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &record, nil

}I wonder why Gorm copies structs all over the place, so I return a pointer. The error about unbounded queries is forced because this method would have to return a different interface depending on whether any options had been given. All of my cases provide at least a Where option so I won’t hit this error.

How it looks in the business layer

This is possibly one of my most complex business calls and is part of the Player Leaves Team business method. I need the player’s current team. I also need to know how many other players the team has so that when this player leaves the team I know whether to withdraw the team from the game.

I also load the game here so that I have information about the game to report back to the user. This business method returns a structure which contains information such as the new team status (playing/withdrawn/completed), any penalty the team will suffer for not completing the game and the team and game names for use in user facing messages.

// Load the team with members (excluding me) and game info

team, err := teamstore.GetByUserAndGame(ctx, userId, gameId,

teamstore.WithPreloadMembers(

stores.WhereP("user_id <> ? AND status=?", userId, domain.MembershipStatusActive)),

teamstore.WithPreloadGame())I could write a function in teamstore to WithPreloadActiveMembersOtherThan(myUid). This may be a good idea as information about field names has leaked into the business layer here.

// Load the team with members (excluding me) and game info

team, err := teamstore.GetByUserAndGame(ctx, userId, gameId,

teamstore.WithPreloadActiveMembersOtherThan(userId),

teamstore.WithPreloadGame())Unit Tests with Mock Database

The static stores mean that I cannot mock out the store layer any more. I need to test against a database. I’m using the in-memory mysql driver to do this. It’s faster, but it risks errors due to differences between the mysql driver and the real Postgresql database. The biggest risk is constraints.

The core infrastructure is a builder

type SetupCommand interface {

Name() string

Command() Visitor

}

type Builder interface {

// WithFurtherSetup creates a new builder with the given setup commands in addition to the existing ones

// The existing builder is not modified

WithFurtherSetup(...SetupCommand) Builder

// Build creates a new MockDatabase instance

Build(t *testing.T) MockDatabase

}Two builder types exist. The Root Builder (rootBuilder is private to this package) has only the list of commands. The Chained Builder has a parent Builder and more commands. This allows me to create a Builder to create the schema I need and another Builder which adds to this with test or test group specific data.

In practice it looks something like this:

// testBuilder creates a builder with all necessary tables for user store tests

var testBuilder = dbmock.NewBuilder(

dbmock.WithUserTable(),

dbmock.WithGamesTable(),

)

var seededTestBuilder = testBuilder.WithFurtherSetup(

// Seed data using command builder pattern

dbmock.NewCreateUserCommand("user1", func(u *domain.User) {

u.PhoneNumber = dbmock.StringPtr("+1234567890")

u.DisplayName = dbmock.StringPtr("Test User")

}),

dbmock.NewCreateUserCommand("user2", func(u *domain.User) {

u.PhoneNumber = dbmock.StringPtr("+9876543210")

u.DisplayName = dbmock.StringPtr("Second User")

}),

dbmock.NewCreateGameCommand("game1", "user1", func(g *domain.Game) {

g.Title = "Test Game"

g.GameCode = dbmock.StringPtr("TEST001")

g.Status = domain.GameStatusActive

}),

)The test then uses the builders:

func TestGetById_BasicLoad(t *testing.T) {

// Setup

mockDB := seededTestBuilder.Build(t)

ctx := mockDB.NewContext()

userID := mockDB.GetValue("user1.ID").(uuid.UUID)

// Execute

user, err := userstore.GetById(ctx, userID)

// Assert

require.NoError(t, err)

require.NotNil(t, user)

assert.Equal(t, userID, user.ID)

assert.Equal(t, "+1234567890", *user.PhoneNumber)

assert.Equal(t, "Test User", *user.DisplayName)

assert.Equal(t, cmdcontext.UserContextInactive, user.CurrentContext)

//...It’s more useful to look at the Team Member setup command, as this shows how commands depend on eachother.

// CreateTeamMember creates a test team member with default values

func CreateTeamMember(db MockDatabase, teamID int64, userID uuid.UUID, overrides ...func(*domain.TeamMember)) *domain.TeamMember {

member := &domain.TeamMember{

TeamID: teamID,

UserID: userID,

Status: domain.MembershipStatusActive,

IsLeader: false,

JoinedAt: time.Now(),

}

for _, override := range overrides {

override(member)

}

err := db.DB().Create(member).Error

require.NoError(db.T(), err, "failed to create test team member")

return member

}

func NewCreateTeamMemberCommand(key string, teamKey string, userKey string, overrides ...func(*domain.TeamMember)) SetupCommand {

return NewSetupCommand(fmt.Sprintf("create team member %s", key), func(db MockDatabase) error {

teamID := db.GetValue(teamKey + ".ID").(int64)

userID := db.GetValue(userKey + ".ID").(uuid.UUID)

member := CreateTeamMember(db, teamID, userID, overrides...)

db.SetValue(key, member)

db.SetValue(key+".ID", member.ID)

return nil

})

}

The pattern of storing key and key.ID allows joins to work.

I’ve used test helper systems in work and they really do thelp. The system I wrote at work for a large project went a layer beyond this. I could ask for any business object and the system would default all of its dependencies for me, so here I’d ask for a Team Member and, unless I overrode them, I’d get a User and a Team and a Game automatically. Here I need to set up the User, Team and Game but this is not hard. The test helper framework is quite simple as a result.

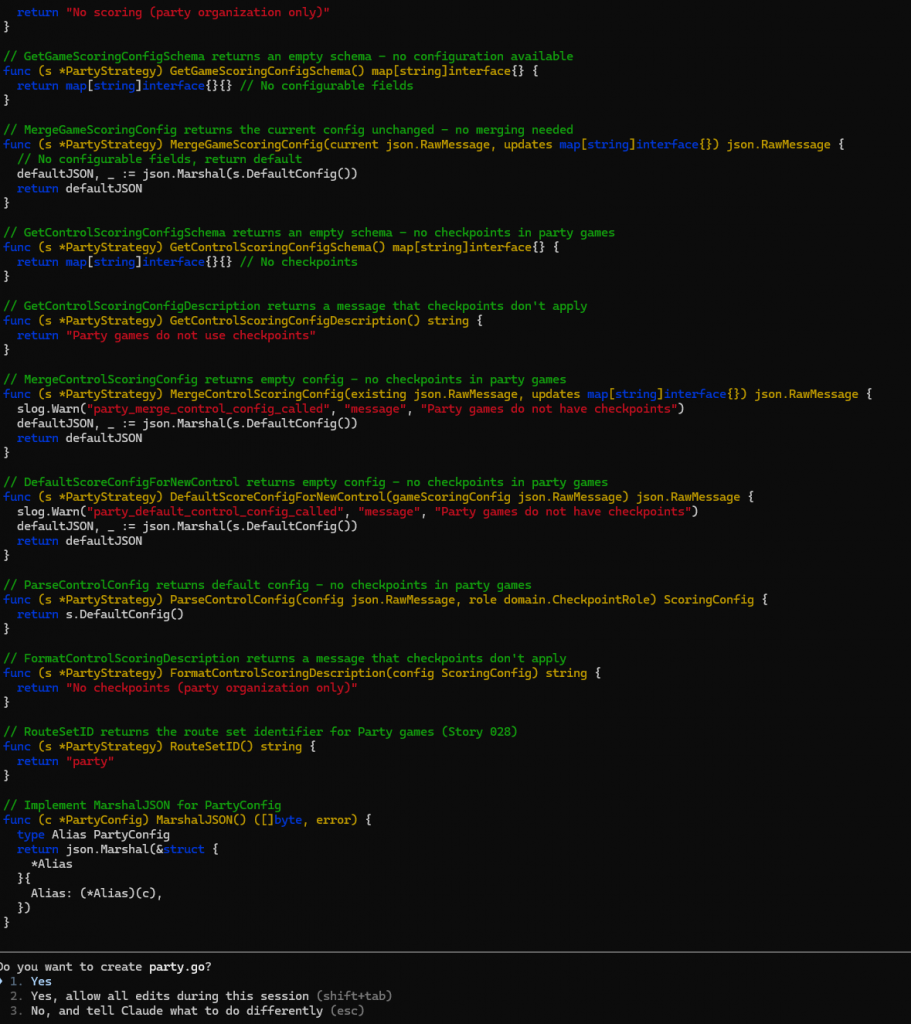

Business Layer – Back to Command Objects

My business layer has returned to using Command Objects over Command Functions. To be fair, I could have likely stuck with functions. The use of objects has allowed a simple mocking framework for presentation layer functions that call a single business method.

var mocks = make(map[reflect.Type]any)

// GetMock returns a mock of the given type and returns true if it exists

func GetMock[T any]() (T, bool) {

typeT := reflect.TypeOf((*T)(nil)).Elem()

mock, ok := mocks[typeT].(T)

return mock, ok

}

// SetMock sets a mock of the given type

func SetMock[T any](mock T) {

mocks[reflect.TypeOf((*T)(nil)).Elem()] = mock

}

// ClearMocks removes all registered mocks

// Should be called in test cleanup (defer) to prevent test pollution

func ClearMocks() {

mocks = make(map[reflect.Type]any)

}My business function uses a factory method to create the Command instance. For example

// LeaveTeamCommand removes the player from the team and returns information about the new state of the team.

// It will execute team state transitions as a result of the last player leaving.

// It will execute user context state transitions, setting the user to idle if they are currently playing in this team.

type LeaveTeamCommand interface {

cmdcontext.Command

Result() *LeaveTeamResponse

}

// NewLeaveTeamCommand constructs a New LeaveTeamCommand for the given user and game.

// It will return a mock instance if one is set.

func NewLeaveTeamCommand(userId uuid.UUID, gameId int64) LeaveTeamCommand {

mock, isMocked := cmdcontext.GetMock[LeaveTeamCommand]()

if isMocked {

return mock

}

return &leaveTeamCommand{

userId: userId,

gameId: gameId,

}

}

The mock is not aware of the parameters passed here. I could improve the framework with a factory pattern that accepts the parameter list and returns a mock instance, or support assertion to capture the parameters. This can all come. For now this simple framework allows me to test my presentation layer without the mock database if I want.