This will be impressive if it works! Using Claude to write a party food organising bot on top of my wide-game-bot framework!

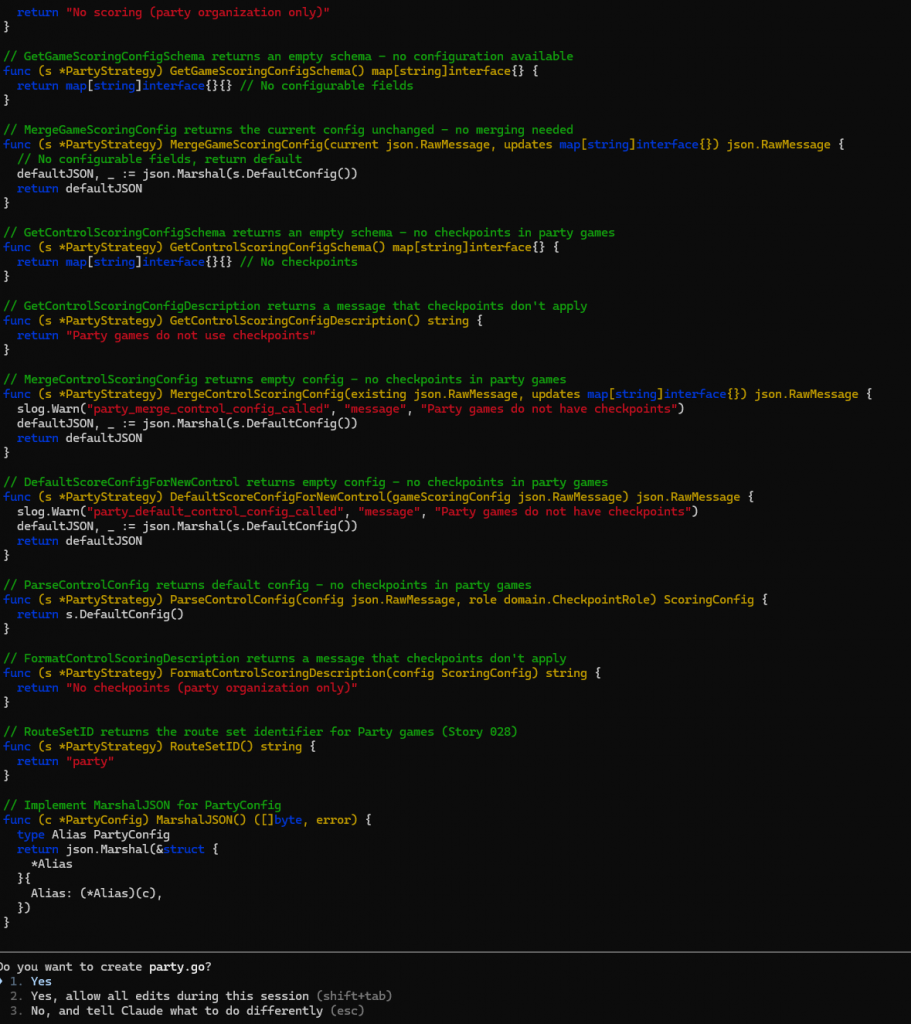

I’ve extended the framework to allow a Game Type to choose the “command routing” taken by the system. It already had fixed command routers depending on player context, “Admin”, “Player”, “Idle” and “Anonymous”. Now I add a concept of a RoutePair which means that my wide games will go to “location-base-game/admin” and “location-based-game/player“. These remain the same, but I add a new “party/admin” and “party/player“.

These routes both inherit the “always” route which allows for joining and leaving a game, and then implement only an AI Assistant. The assistant has tools to get the party menu and allow a player, er…., participant to specify what they are bringing.

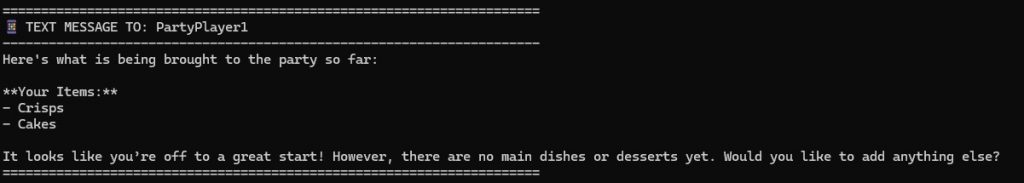

Players Participants can only see their own food and that someone else is bringing crisps and nibbles. The game admin can see the entire menu alongside who is bringing what.

This is a great thing about Strategy Pattern. I’ve just added a new Game Type Strategy which plays a very different game to anything I imagined when I started this project.

Findings as I implement this

Teams!

The existing games are in teams. The architecture assumes that a player is part of a team and a team is in a game. This means that party participants also have to be in teams! This could work well. “The Smith Family” could have both parents contributing to the same food list. It also means that a participant chooses their display name. I was going to use their WhatsApp display name. The system uses AI to moderate these. I’ll have to have the AI moderate their food choices too!

Other people’s ideas?

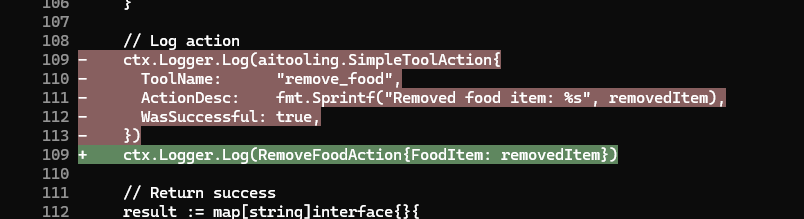

I imagine other people are solving the problems I’m solving. I’ve never had a SimpleToolAction, but the idea here is interesting and maybe I can learn from it.

I should have stuck to Stores

I discussed store pattern in Experiments in Go – Three Tier Architecture in a WhatsApp Game-Bot and decided to move from a Store pattern with manual SQL to using Gorm directly in code. I’m learning now that I should have stuck to Stores, and will write up more on this later.

Claude keeps looking for Stores. I don’t know if that’s from remains of documentation about the pattern in the codebase docs folder, or because everyone does Stores. The final architecture would be Stores with Gorm based store implementations but that will be a large refactor (oh no not again!). I’m finding the domain package is filling up with Store methods. I also want to be able to swap in things like a REDIS store for objects like the mementos used to track multi-step user conversations.

A Prompt Injection Attack! (Sort of)

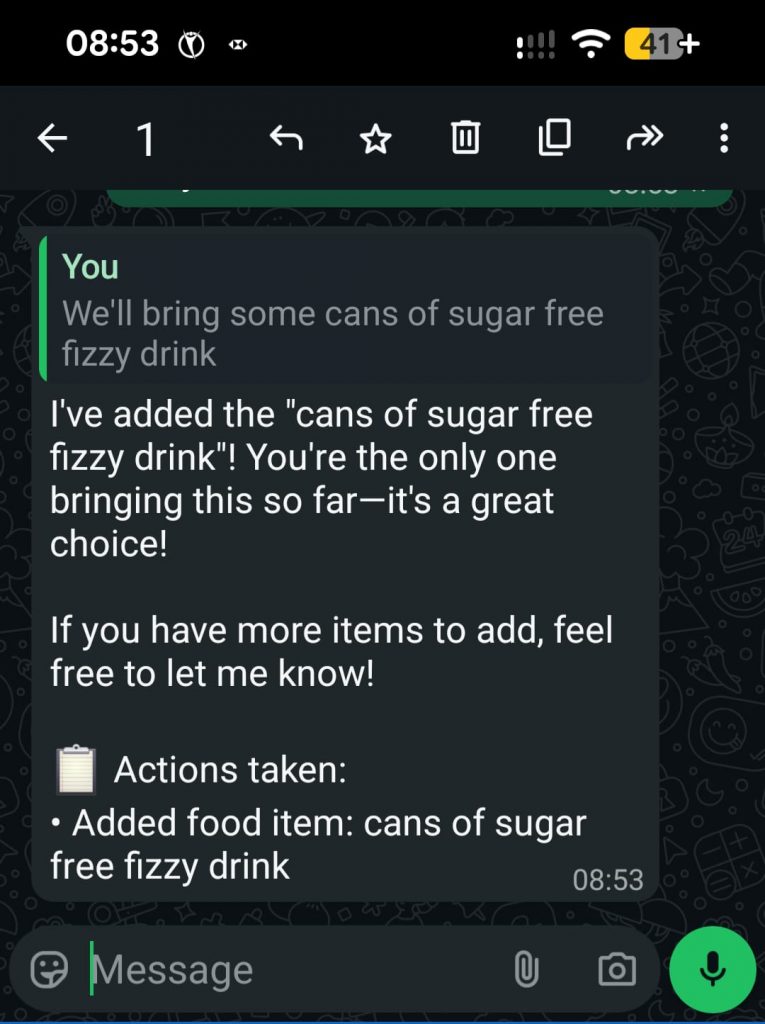

I’d initially intented it not to be possible for participants to see who was bringing what. In retrospect this was an anti-feature. People are discussing this over WhatsApp in the Parents Channel. When I wrote the wide-game-bot I’d designed the player tools to make it impossible for the AI to do anything the player should not do or access information that the player cannot access. Claude’s rapidly written “list_food” tool returns the food items along with the name of the teams that bring them.

I noticed this when a parent asked me to add a food item on their behalf. So I added specifically “Crisps (Eliot)”. The AI then started including team names for all of the other items in brackets when listing foodstuffs!

So my food item was

{

"food":"Crisps (Eliot)",

"team":"Sparks and James"

}Every other item was

{

"food":"Drinks",

"team":"The Smiths"

}The AI formatted that one as “Drinks (The Smiths)“.

It’s an easy bug to fix, but I’ve not fixed it because I think it’s actually a feature. If Claude had followed my original intent and prevented acccess then I’d have been tempted to add it in!

My wide game players still cannot see whether territory is owned by any other teams before entering it and risking a penalty, or in the simple Score game they cannot see which bases have been claimed already.

Conclusion

I have a party-bot. It was developed very quickly, a few hours including refactoring the Game Strategy to allow complete user input routing override through the existing Command Router System and debugging.

I have a lot of technical debt and a large TODO file to clean it all up.

I’m about to test this all for real by sharing it with my Scout parents!

Is Conversational AI the new User Interface?

I’ve got used to it and find it natural. Will my users? That’s a big question. This could be crying out for a quick website solution, something which I may well add! Then I’ll have a web site and WhatsApp user interface to the same backend data which will be neat.

I can imagine a world in which conversational UI is the norm. It seems full circle, back to the command line, but with voice recognition. “Hey – Party-Bot – We’re bringing cake!” – possible now if someone presses the “voice input” button on their phone.

The web site would also have a place. This is a problem that just calls for tabular data and an “add row” button.

References

This is the AI Assistant supporting code from the project:

https://github.com/m0rjc/goaitools

I hope to publish the WhatsApp ingress and egress code when it is in some kind of shape to be shared. At the moment it has no egress rate limiting, which is a risk. The chance of me exceeding WhatsApp limits with a small party of Scout parents is low, so I take that risk.